Following the release in May 2013 of the report of the Inquiry into the Operation of Queensland’s Workers’ Compensation Scheme, the Workers Compensation Rehabilitation & Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2013 was passed on 17 October 2013.

Significant changes were made to the Queensland Workers’ Compensation and Rehabilitation Act 2003 (‘the Act‘). The Act was assented to on 29 October 2013, and the changes are now in effect.

The purpose of the changes was to “strike a better balance between providing appropriate benefits for injured workers and ensuring the costs incurred by employers are reasonable“. Whether that goal will be achieved and whether the number of claims will decrease, is yet to be seen.

The purpose of the changes was to “strike a better balance between providing appropriate benefits for injured workers and ensuring the costs incurred by employers are reasonable“. Whether that goal will be achieved and whether the number of claims will decrease, is yet to be seen.

Regardless, it is critical that employers remain vigilant with the workers’ compensation process and understand their rights and obligations to deal with the changes, and to defend against claims.

The Queensland scheme

- The laws aim to ensure Queensland maintains the leading workers’ compensation scheme in Australia.

- Queensland is the only state where ALL workers are covered during their journey to and from work.

- The changes are to ensure that the premiums paid by businesses will be the lowest in Australia.

- Queensland has the lowest common law threshold of any state in Australia (for example – Queensland’s starting threshold is greater than 5%, while Victoria’s is 30%. South Australia, the Northern Territory and the ACT have abolished workers’ rights to make common law claims).

The key changes include:

- Replacing Q-Comp with the “Workers Compensation Regulator” and merging it into the Office of Fair and Safe Work Queensland. The explanatory notes regarding the change identify that the Workers Compensation Regulator will operate in a similar manner to the regulator under the Work Health & Safety Act 2011.

- Allowing employers to seek disclosures from prospective workers about previous injuries/conditions and obtain their workers compensation claims history.

- To make a common law claim a worker must now have a 5% Degree of Permanent Impairment (‘DPI‘) arising from the injury, which replaces the concept of whole person impairment.

- The table of injuries has been removed from the Workers Compensation and Rehabilitation Regulation 2003 and replaced with a new calculation for lump sum compensation under the relevant DPI.

- The definition of “injury” under section 32 of the Act, has been amended.

Who can make a common law claim for work related injuries?

The Act now contains a threshold the worker must meet so to make a common law personal injury claim in relation to a work related injury sustained on or after 15 October 2013.

The concept of “work related impairment” has been replaced with a method of assessment of “degree of permanent impairment” (‘DPI‘).

Workers are now only able to file a common law damages claim for a work related injury where a worker’s DPI is assessed as being greater than 5% or, who have a terminal condition. Dependents retain their ability to seek damages if the work related injury resulted in the worker’s death.

[Workers who sustain an injury prior to 15 October 2013 will have their workers compensation claims processed and dealt with under the old provisions of the Act.]

What is an “injury”?

The definition of “injury” in relation to physical injuries remains unchanged. For physical injuries, employment still needs to be “a significant contributing factor” to the injury.

However, the definition of “injury” in relation to psychiatric or psychological injuries has changed to require that employment be “the major significant contributing factor to the injury”. This change will represent a higher threshold to be met by claimants seeking compensation for psychological injuries.

The exemption of psychiatric/psychological injuries arising from reasonable management action taken reasonably in relation to the worker’s employment remains unchanged.

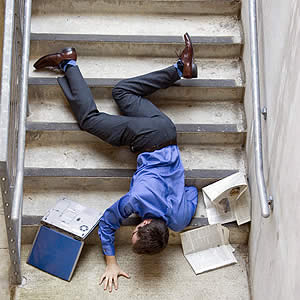

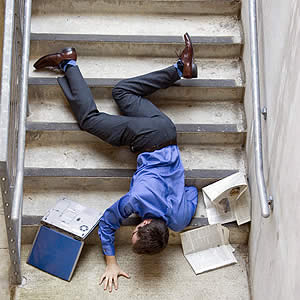

Workers also remain able to make journey claims (injuries that occur during certain journeys).

Employers to Seek Disclosures to History

From 29 October 2013, prospective workers, upon receiving a written request by a prospective employer, are required to disclose all pre-existing injuries of which they are aware could reasonably be aggravated by performing the duties of the position they applied for.

A prospective employer must advise the prospective worker:

(a) Of the nature of the duties the subject of the position he prospective worker has applied for; and

(b) that if they do not comply with the request, or they supply false or misleading information, the worker will not be entitled to compensation or damages under the Act for any event that aggravates the non-disclosed pre-existing injury.

Where the prospective worker fails to disclose relevant pre-existing injuries or provides false or misleading information and aggravates the non-disclosed pre-existing injury, the worker will lose their entitlement to compensation and damages.

For employees who were engaged before being requested to make the disclosure, their ability to make claims for pre-existing/non-disclosed injuries remain unchanged.

Furthermore, with the consent of the worker, and payment of a fee to the Regulator, a prospective employer is now able to access a prospective worker’s claims history summary. The amended Act provides that the prospective employer must maintain confidentiality of the summary and not disclose the contents. The summary may only be utilised with respect to considering and selecting the prospective worker for employment.

However, the prohibition in the Act on obtaining and using “workers’ compensation documents” (as defined in the Act) for selecting a person for employment or determining whether a workers’ employment is to continue, still exists. The application of the Fair Work Act 2009, and discrimination laws, also continue to apply. Hence, access to information about a prospective worker’s workers compensation history and pre-existing conditions will need to be carefully managed and considered in order to ensure legal compliance.

Now What?

Employers need to understand the implications of the recent amendments of the Act, in order to defend against workers’ compensation claims.

While significant changes have been made, key processes and obligations under the Act remain unchanged, including, employers having 8 business days to provide a response to a workers compensation claim to the insurer.

Employers should ensure that policies and procedures:

(a) maintain reasonable management action;

(b) meet work, health and safety requirements, to minimise injuries;

(c) address access to medical and workers compensation documents and use of those documents.